Member Directory,

1847 - 1922

Jackson E. Reynolds

Lawyer

Centurion, 1914–1958

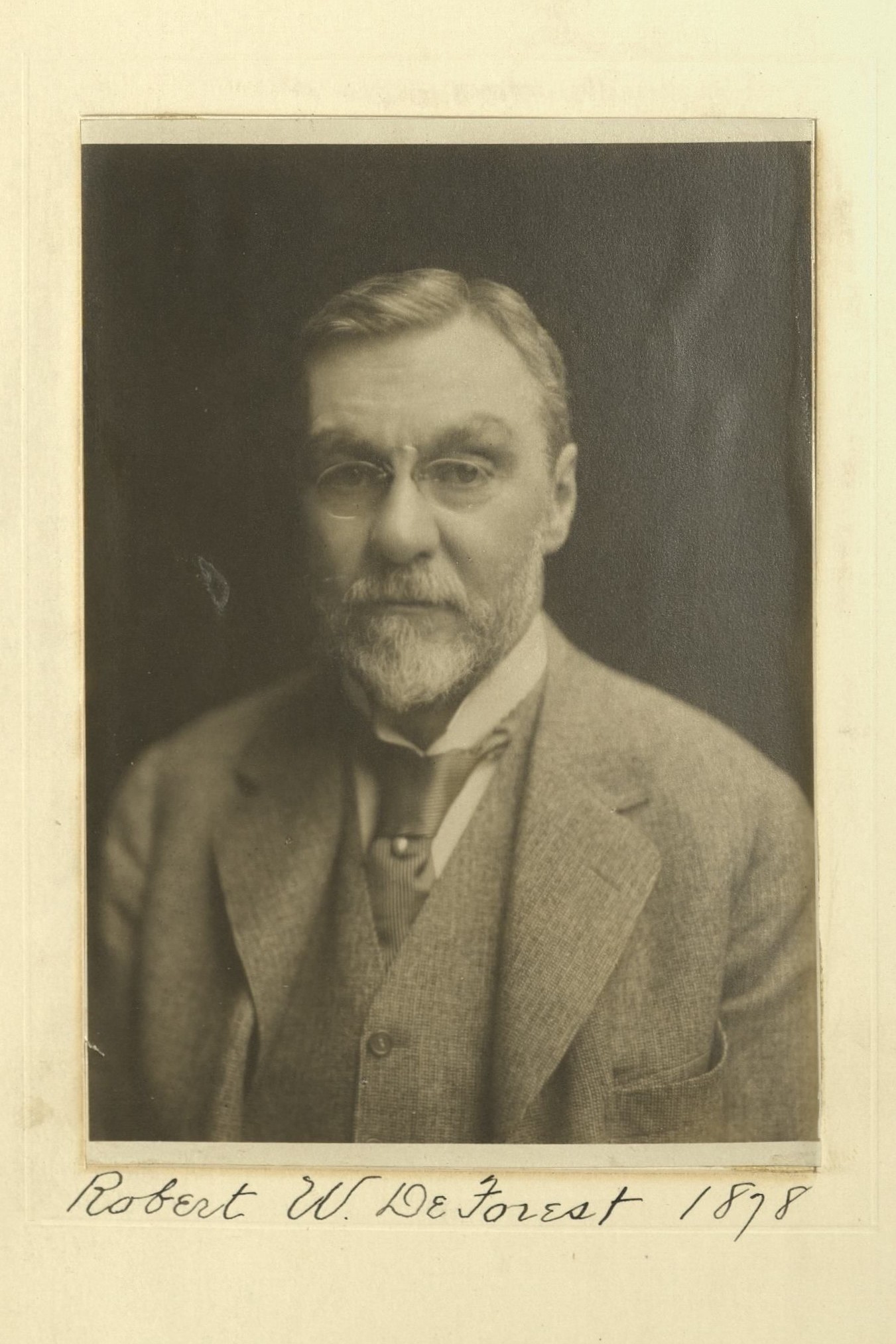

Nathan Abbott and Robert W. de Forest

Woodstock, Illinois

New York (Manhattan), New York

Age forty-one

Century Memorial

Jackson Reynolds graduated from Stanford in 1896, and from the Columbia Law School in 1899. He started his career as a teacher of law, spending two years at Stanford and eight at Columbia, and then he actively practised law, becoming involved in antitrust and interstate commerce matters and defending railroads against the attacks of the Government and minority stockholders.

In 1917 he became a director and vice-president of the First National Bank. This institution had a countinghouse, known as “Fort Sherman,” at 2 Wall Street, and it had only 1,200 depositors—but they each kept minimum balances of $100,000, and some of them of many millions. It was a whole sale bank, and firmly managed by Mr. George F. Baker, who was born in 1840 and had been through every panic and depression since 1857. He complained that they changed the rules a little with each new one. Mr. Baker was interested in young men, and was training Frank Hine to succeed him as head of the bank; but Hine died of old age in 1927; so then Mr. Baker began to train Jackson Reynolds for the place.

Reynolds was president of the bank till 1937, when he retired, full of honors and years; but a month later Mr. Baker himself died at the age of 97, and Reynolds had to come back and be Chairman of the Board till 1939, when he succeeded in abolishing the office entirely and again retiring. He then sold his house in Beekman Place, one of the last of the imposing private houses built before the depression years, to Billy Rose and moved into a modest apartment on Park Avenue.

It must be said that whatever Jackson Reynolds put his hand to he did extremely well and seemed to have a good time doing it. It was impossible to disturb his aplomb. He had a dead-pan face that took good news and bad without change of expression, and he approached difficult problems without any sign of discomposure. His relations with Mr. Baker were necessarily very close over a long time, but he never complained of the old man to anyone. He seemed to regard him as a unique and valuable curio to be listed among the assets of the bank.

With all the turmoil of two wars and the 1929 debacle and its consequences, Reynolds found time to serve as a director of the Federal Reserve Bank, Chairman of the Clearing House, Trustee of Columbia, and in a host of other consecrated jobs—some of which (like renting the Columbia lease-hold for Rockefeller Center) consumed an untoward amount of time and effort. He was humorously detached about these things, and not in the least dedicated to good works. When he saw something that was important and had to be done, he went and did it—not rejoicing at this opportunity to serve his fellow-citizens, but complaining gently that Chance or an all-wise Providence had selected him. But he always did it.

When the Lord shall come and reckon with Jackson, he will say: “Well done, thou good and faithful servant.” And Reynolds, with less composure than usual, will murmur: “Please don’t mention it.”

George W. Martin

1959 Century Association Yearbook