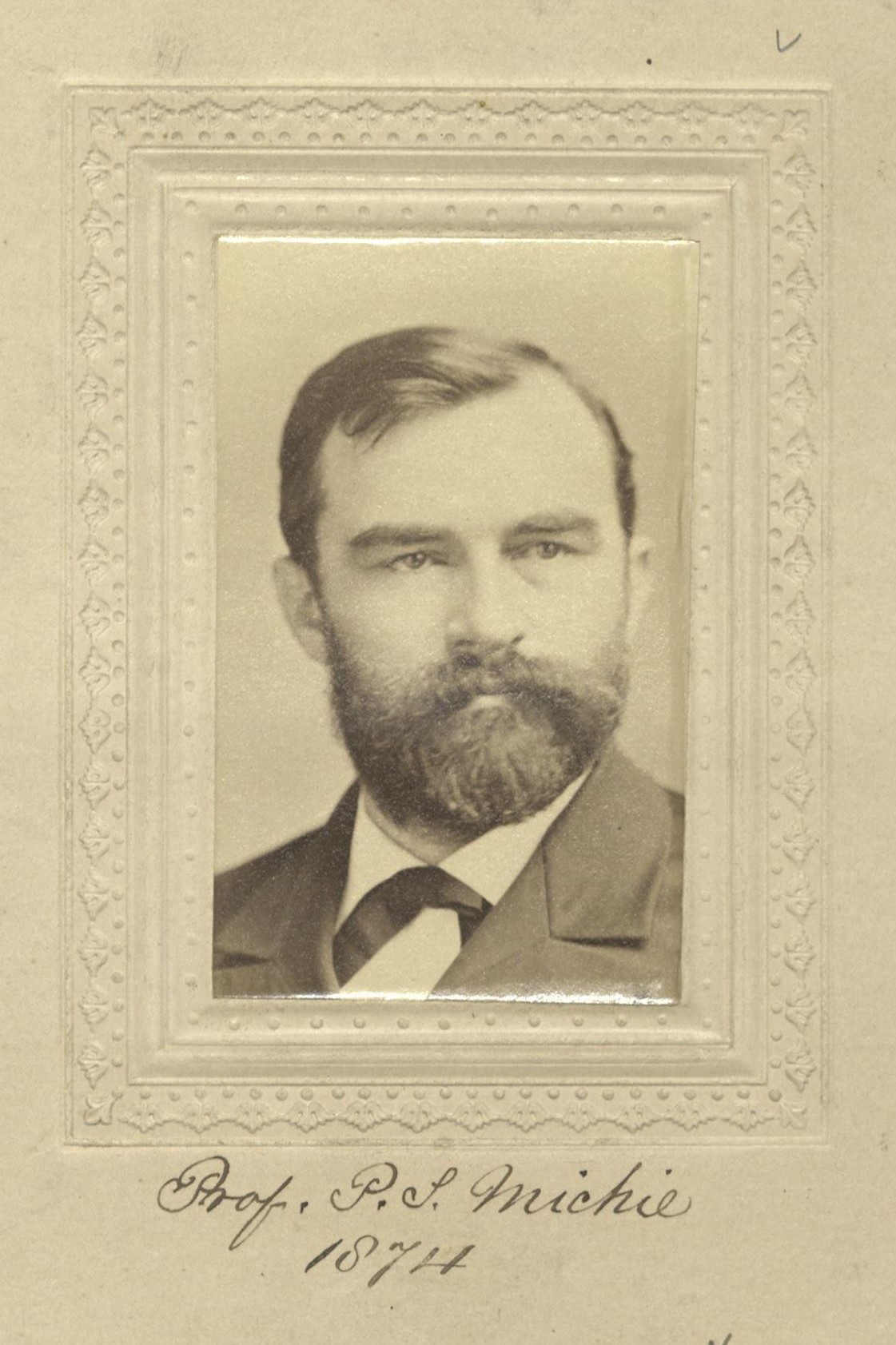

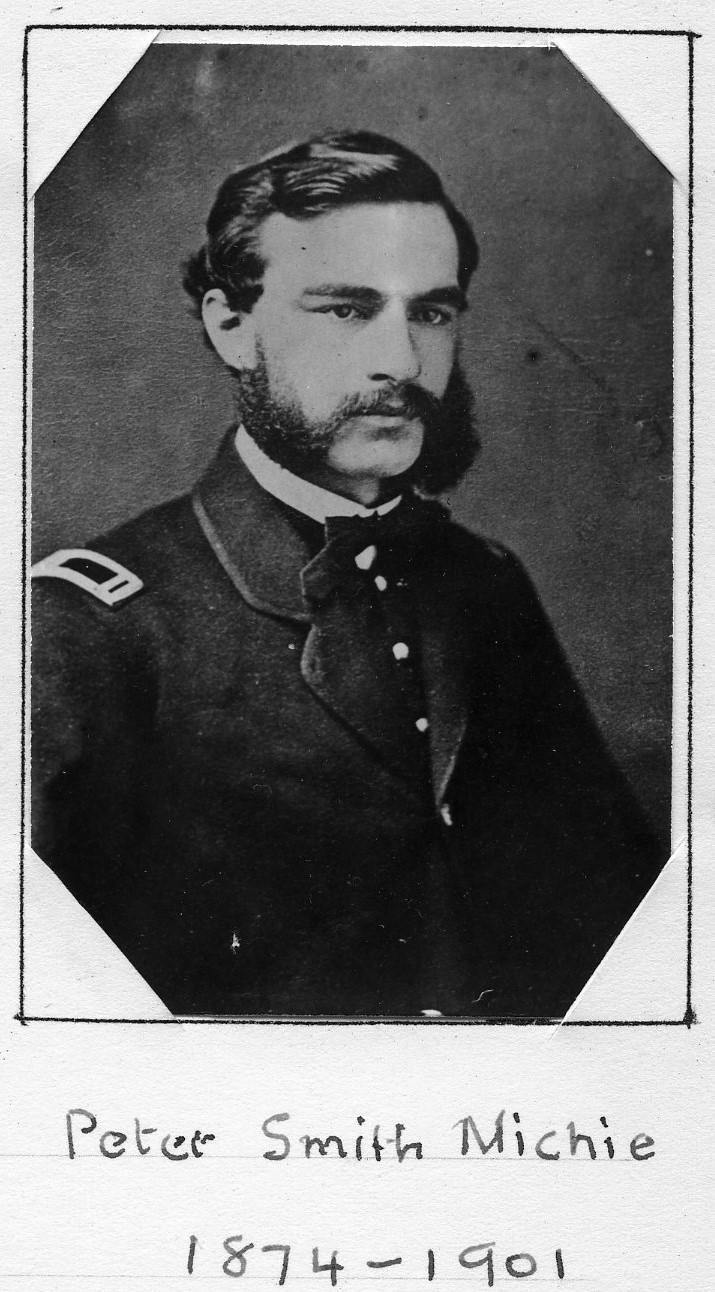

Army Officer/Professor, West Point

Centurion, 1874–1901

Born 24 March 1839 in Brechin, Angus, Scotland

Died 16 February 1901 in West Point, New York

Buried United States Military Academy Post Cemetery , West Point, New York

, West Point, New York

Proposed by John Durand, Charles Walker Raymond, and William Conant Church

Elected 7 November 1874 at age thirty-five

Proposer of:

Seconder of:

- George F. Barker

- Edgar W. Bass

- Thomas Lincoln Casey

- Cyrus B. Comstock

- Wright P. Edgerton

- George C. Freeborn

- Arthur Sherburne Hardy

- Walter McFarland

- John Brisben Walker

- John Philip Wisser

Supporter of:

Century Memorial

Among the first of the members of The Century to drop from the loved circle was Professor Peter Smith Michie. For more than a quarter of a century he rarely missed a monthly meeting. He had what cannot be defined or mistaken—the Century habit. He found here, as he brought hither, the subtle charm of constant friendliness. Modest, kindly, of vigorous mind and wide experience, sound and penetrating in judgment, independent in opinion but open-minded, a formidable disputant but little inclined to contention, merry as a child when mirth was in the air, his was

“a summer mood,

As if all needful things would come unsought

To genial faith, still rich in genial good.”

Colonel Michie entered the Military Academy from an Ohio district in 1859, at the age of twenty-one. Graduated in 1863, he immediately sought active service in the field, and was assigned to duty in connection with important engineering operations then in progress in the Department of the South. He was in charge of the siege approaches which, resulted in the reduction of Fort Wagner in Charleston Harbor in 1863; he accompanied the Florida Expedition as Chief Engineer, and was engaged in battle at Olustee, Florida, on February 20th, 1864. At the opening of the campaign in Virginia in 1864 he was assigned to duty at the Headquarters of the Army of the James, and was actively employed as Chief Engineer of that army in the operations against Richmond. He took an active part in the engagements at Drury’s Bluff in May, 1864; in the assault and capture of Fort Harrison, September 29th, 1864; and in the final campaign which terminated in the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House on April 9th, 1865. Professor Michie received the brevet of Brigadier-General of Volunteers, and also those of Captain, Major, and Lieutenant-Colonel in the regular army for gallant and meritorious services. After the close of the war he was employed for a year in making a survey of the theatre of war around Richmond, and, after a year’s leave of absence, he was appointed instructor at the Military Academy and, in 1871, professor. His service there was continuous until his untimely death at the age of sixty-three. He was the author of several works in his own specialty, and of a “Life of General Upton,” a “Life of General McClellan,” published after his death, and he left nearly completed a “History of the Military Academy.” In the General Order issued from the Headquarters of the Academy at the time of his death, Colonel [Albert] Mills, the Superintendent, bears testimony to “his capacity and excellence as a soldier,” his “ability as an educator,” his “strong, unwavering religious faith,” his “unblemished daily life, his sound and helpful advice, and his abounding sympathy.” “To the graduates of more than a generation,” says the Order, “he stands as the embodiment of all that was best and most helpful in the traditions of the Institution which his life and public services have done so much to render illustrious.”

An anecdote is related of Professor Michie by a fellow officer in the war for the Union, illustrating the high moral courage of the man. In his second year of service he had ridden with the Commanding General and his staff in advance of the position of the army to reconnoitre. It was soon seen that the group was attracting the attention, and would be exposed to the fire, of a battery of the enemy. The General was urged to retire. Somewhat impatiently, he replied that if any gentleman was afraid he had permission to retreat. Major Michie responded: “As the Chief Engineer has no duties to perform at this point, and as I am quite ready to admit that I am afraid, with your kind permission I will go back.” He had gone but a short distance when the General and his staff overtook him at a gallop, two of the staff riding on one horse, the horse of the extra rider having been killed by a shot from the enemy’s battery. The young West Pointer, calmly facing the odium of implied cowardice in the discharge of what he knew to be his duty, was an example of the truest and finest bravery. He lived to win from his superior officer the highest praise, creditable to both.

The closing years of Professor Michie’s life were darkened by great grief. His son, Lieutenant Dennis M. Michie, fell at the battle of San Juan. A second son died from typhoid only two months later. These ills the father bore with the heroic patience of his pure and trusting spirit, but they hastened the end. He passed away on the 16th of February, 1901, the faithful and gallant officer, the wise, kind teacher, the beloved friend,

“Whose powers shed round him in the common strife

Or mild concerns of ordinary life,

A constant influence, a peculiar grace;

But who, if he be called upon to face

Some awful moment to which Heaven has joined

Great issues good or bad for human kind,

Is happy as a lover; and attired

With sudden brightness, like a man inspired.

This is the happy warrior; this is he

That every man in arms should wish to be.”

Edward Cary

1902 Century Association Yearbook