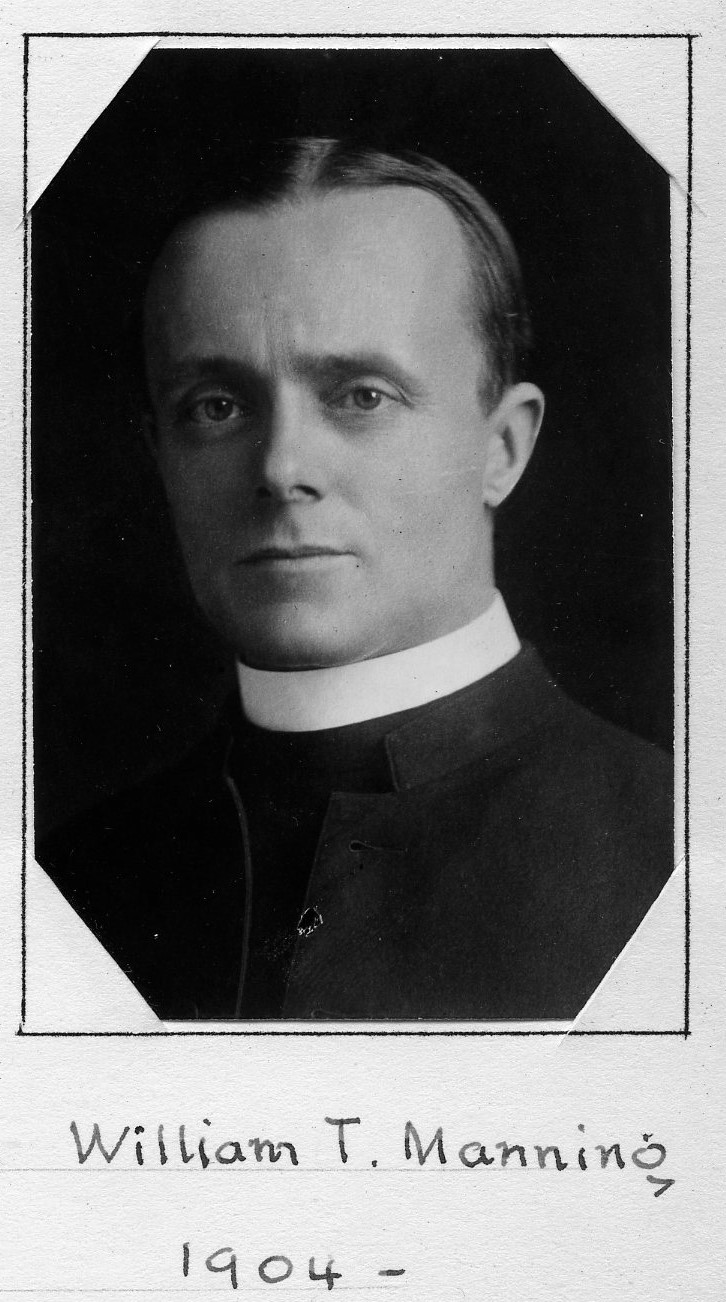

Clergyman

Centurion, 1904–1949

Born 12 May 1866 in Northampton, England

Died 18 November 1949 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Buried Cathedral Church of Saint John the Divine , Manhattan, New York

, Manhattan, New York

Proposed by Francis Sedgwick Bangs and John H. Caswell

Elected 4 June 1904 at age thirty-eight

Seconder of:

Century Memorial

William Thomas Manning. [Born] 1866. Clergyman.

Bishop Manning will live in history for his contribution to the whole Anglican Communion, as probably the greatest Cathedral builder since William of Wickham, and as the churchman primarily responsible for the start of the World Conference on Faith and Order. Many of his now-famous battles doubtless will be forgotten: time and moral laziness will shade the starkness of a mind which his contemporaries knew always to see black or white, but never gray.

But we here wish to know what a man was, rather than what he did.

He was, in essence, I think, a soldier, and yet he was a softly sympathetic general, like one of Napoleon's marshals with his troops. In his character of soldier, he was incredibly fearless—a fearlessness doubly revealing when it be understood that he was a thin-skinned man. For the fact is that no man enjoyed being loved more than did Bishop Manning. In every instance of a great public row, his colleague could sense the Bishop calmly making up his mind that it was his duty to be righteous, no matter what it cost him, or anybody else.

One of his dearest friends, in speaking of him as Bishop of New York, said he should have been an officer of the heavy artillery: what he meant was that the Bishop, in public controversy, was a master at the control of fire power. And so he was; but the fact is also that he had extraordinary sensitivity to the public conscience, and often his opponents learned that the Bishop’s reaction to any matter was likely to be that of the average decent American. The Bishop was right, frighteningly right, about ninety-nine percent of the time. When he was wrong, he was almost unequalled—as Mayor La Guardia once confessed about himself: “When I make a mistake, I make a beaut.”

Of his kindness as Bishop of New York one heard little until after he had retired, and that kindness passed all bounds. Whenever an official memorandum went out at the Cathedral reminding the clergy that the Cathedral was not a parish and that welfare problems and aid should be administered by the parishes, his staff all knew just one thing—that it was not that any one of the Cathedral clergy had acted contrary to this rule, but rather that the old Bishop himself had just given away so much more money than he had, that this was his way of compensating his conscience.

The Bishop had the quality which distinguishes all great men—he viewed his position objectively and himself with humility. There was an almost incredible contrast between the Bishop of New York in his office—the austere, forceful man who gave worry to politicians and rubric-breaking curates, and courage and protection to the poor and the helpless—and Dr. Manning in his home—simple, shy, with engaging humour and a saving dash of irrationality.

The Bishop had an almost fierce joy in stories about himself. His native honesty was such that the stories never grew or got more elaborate as time went on and anyone who travelled with him officially had good opportunity to know this because the Bishop told his favorite stories often, and always with great effect. His two favorites were these:

After some public speech of his, the Bishop received a message from a woman in Virginia which concluded, “I am a good Christian woman which I doubt very much if you are.”

The second was the card sent the Bishop by a mid-western boy who had been taken on an official tour of the Cathedral. The card said, “This Cathedral has a bigger knave in it than St. Peter’s in Rome.” The Bishop used to remark after that, “I like that story—it cuts both ways.”

It was his sturdy faith, however, and his loyalty to the Church which marked him most. The loyalty to his Church made him a great bishop.

What made him a great man was the goodness of his personal life and his abiding sense that the Church existed to serve God’s people. No more touching or fitting tribute to the Bishop could be composed than his own statement of the faith he lived:

“The Christian Religion . . . is a life lived in personal, daily, conscious relationship with him Who died for us on the Cross, Who rose from the dead, and Who now lives for us in Heaven and ministers to us in His Church here on earth.”

If all of this conveys to you the affection and admiration which those who knew him well had for this utterly stern and incredibly sympathetic old soldier, I shall have done well.

Source: Henry Allen Moe Papers, Mss.B.M722. Reproduced by permission of American Philosophical Society Library & Museum, Philadelphia

Henry Allen Moe

Henry Allen Moe Papers, 1949 Memorials