Architect

Centurion, 1894–1941

Born 13 February 1856 in Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts

Died 8 August 1941 in Bar Harbor, Maine

Buried Grove Hill Cemetery , Waltham, Massachusetts

, Waltham, Massachusetts

Proposed by William Rutherford Mead, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and Thomas Tryon

Elected 3 November 1894 at age thirty-eight

Proposer of:

Century Memorial

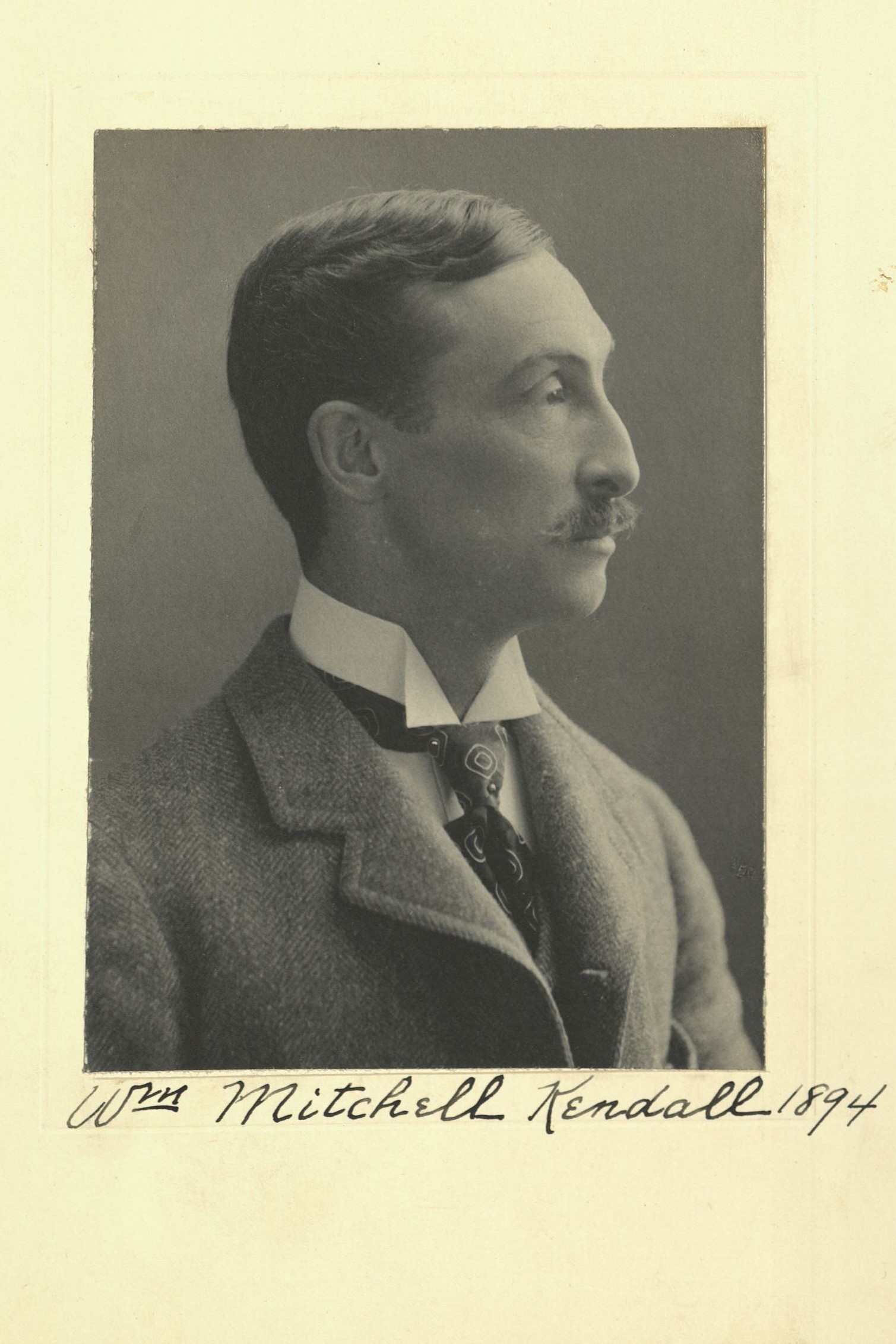

William Mitchell Kendall

The son of a scholar, William Mitchell Kendall had scholarship in his blood and it may be said to have predestined him to enter, as far back as 1882, the illustrious firm of McKim, Mead and White. He had had appropriate preparation. He had been educated at Harvard, where he came whole-heartedly under the sway of Charles Eliot Norton. Following upon his graduation in 1876 he studied architecture for two years at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Then came exploration of the monuments in Europe. All his experiences tended to confirm his predilection for tradition and good taste. When he began his professional career in association with the architects just mentioned his role was fixed. He was a superior draftsman and designer, who became the right hand of McKim, and in due course he rose to close alliance with the firm. He was finally its senior member, surviving his three memorable partners. When death touched him at Bar Harbor, in his eighty-fifth year [sic: in his eighty-sixth year, i.e., at age eighty-five], it ended a life that had been “all of a piece,” wreaked successfully upon his art, under one banner of collaboration and friendship.

It was a long life and toward its close Kendall suffered from some of the disabilities of age, among them a deafness which sadly handicapped him in conversation. But those who knew him in his young manhood and in his prime preserve only the memory of one of the most charming Centurions ever known in the Club. His talk was singularly animated and interesting, into which constant flashes of humor brought a specially endearing quality. Kendall was a deeply cultivated man, a discriminating reader, an ardent lover of music, particularly of opera, and a tireless traveler, visiting Europe over and over again in the course of his long and busy life, always with a passionate interest for the great landmarks in architectural history. Greece and Italy were to him sacred places.

In Rome he breathed what was in some sort his natural air. He loved not only the grandeur of the city but everything that contributed to its beauty, its fountains, a garden beyond the gates, or a molding on the Cancelleria of Bramante. One who shared in some of his Roman wanderings recalls the sheer joy that Kendall found in them, the ebullient spirit, the humanizing touch with which he seemed somehow to make more approachable the heroic aspect of the great memorials of the past. Tradition was not for him a narrow formula but the free and timeless legacy of the masters, a legacy left not only for our instruction but for our delight, a legacy of beauty, in a word.

To make a structure beautiful was Kendall’s undeviating ambition and that ambition he realized in such works as the New York Post Office, the New York Municipal Building, and the remarkable Arlington Bridge at Washington, a bridge that is remarkable because it is as graceful as it is monumental. That fusion of qualities was characteristic of him. He had an equal control over mass and over detail, seeing that both had fineness in his designs. He could be grandiose but he could not be heavy-handed. So in the intercourse that caused him to be cherished by his friends there was a well-balanced mingling of knowledge and pure playfulness. He would pass from the discussion of some high-erected topic to light talk about the novelists of the moment and in both fields he spoke with authority and beguiling pleasantry.

He received many honors. He was chosen to design the memorial in Rome to the American soldiers who died in the great war. In 1928 the New York chapter of the American Institute of Architects awarded him its gold medal for “distinguished work and high professional standing” in architecture. He was elected a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1929. He was a charter member of the American Academy in Rome and at the time of his death had been its second vice-president for twelve years. Many tributes to him might be cited. But a tribute by itself remains, that which lies in the affectionate remembrance in which he will long be held by his fellows in the Century.

Geoffrey Parsons

1941 Century Memorials