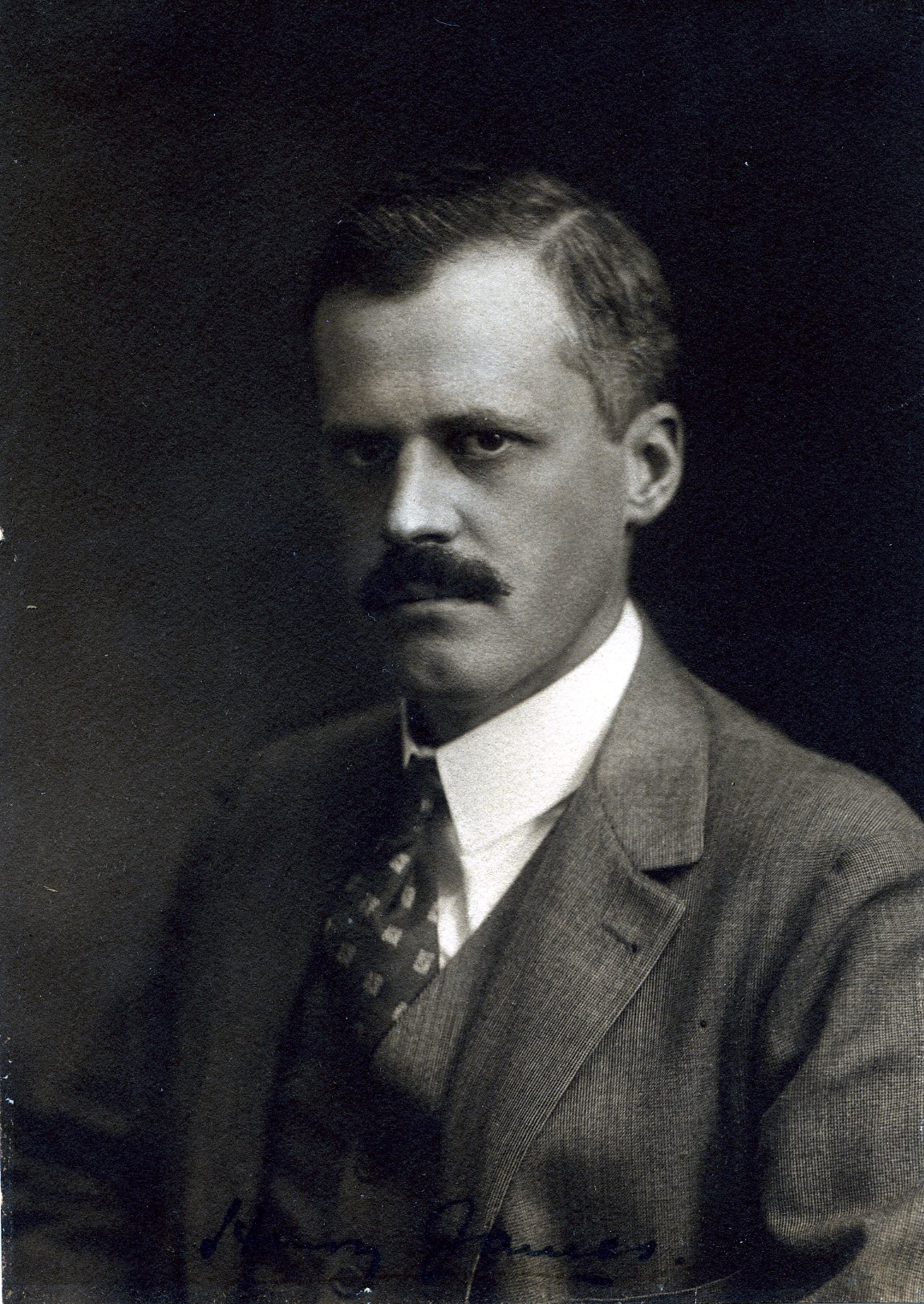

Manager, Rockefeller Institute

Centurion, 1913–1947

Born 18 May 1879 in Boston, Massachusetts

Died 13 December 1947 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Buried Cambridge Cemetery , Cambridge, Massachusetts

, Cambridge, Massachusetts

Proposed by Dickinson Sergeant Miller and John Graham Brooks

Elected 1 November 1913 at age thirty-four

Archivist’s Note: Nephew of Henry James Jr.; grandson of Henry James

Century Memorial

Henry James. 1879. [Born] Lawyer, scholar.

Those of us who were in the Century when the news came of Harry James’ illness will remember the hush that settled down over the Long Table, the small tables, into the Library, over all—the hush of men thinking hard and remembering. But a mood of such intensity cannot last long and soon we were talking, and we were talking happily. We were recalling Henry James in the Century: we were speaking of him with respect, certainly; we were mentioning him with admiration, of course; but most of all we showed our affection and our feelings. Something of this I wrote to him, diffidently, when the first shock of his illness had passed and I got back a letter I shall always remember:

“Nobody ever had a kinder thought or put it in a note better calculated to warm the heart and brighten the spirits of the recipient. Many, many thanks to you and also to the kind unnamed friends for whom you profess to speak and whose numbers I keep multiplying self-complacently. I wish I might see them all and I hope to before very long. They’ve untented me and are beginning various amusingly trivial processes of hardening me; so don’t let anybody think I shall be shelved for very long.”

This, of course, is Henry James; wholly understood I think it is most of Henry James. It would be infinitely difficult for me to say more; but I have had superb help and with it I can proceed:

Integrity was the kernel of his character and personality, an integrity of approach to things moral, of course; but also, the same instinctive approach to every other matter. This is scarce in our present world. We have high-minded men. But the brittle quality which so often limits the high-minded was completely absent in Harry James. It was a New England shrewdness combined with a depth of sincerity that made his value to others unusual. There was nothing fragile in the alloy. It was metal that rang wholly true.

This was why after becoming irked with the smallnesses of the law, he found his real field as adviser or administrator in matters of public service. Fine brain that he had, it was his simple and essential qualities of character even more than his brain that made him so strong a pillar and so effective a contributor to groups and institutions that served the public interest. He had the breadth of interest that characterizes his family and to which a geographical locality meant no chain.

From his father’s home in Cambridge, he went through Harvard as an undergraduate, through her Law School, then nearly a generation later, began service as Overseer for twelve years, and finally as one of the five Fellows of the Corporation for nearly another twelve. From time to time came literary work, of which the most outstanding was the biography of Eliot in 1930. Service with the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research, with the Carnegie Corporation, as chairman and president of the Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association, were only high-spots in a multitude of activities where the target was invariably service in social or cultural terms.

The metal rang wholly true. It also had a timbre all its own. That this was rich and deep was almost of course—for the metal, after all, came from a forge that was worked by the gods.

Perhaps because of Harry James’ reserve and sometimes dour manner, his expression of his deep sense of the humanities and of the humor that was always lurking just beneath the surface, had special spice. His talk had uncommon range and was highlighted by a concise use of words and a liberal injection of story or anecdote. These last were many and good, but not unique. Yet why do we remember so exactly the conditions under which they were told? By his fireside, walking through his woods, at our own Long Table, he was ever the friend who stood foursquare, as quiet and understanding and farseeing in storm as in fair weather.

In the Century, he was all this and more too. He made our library the good library it is and he wrote a perfect piece on it for our Centennial book. But most of all we owe to him what has come to be known, reverently, as the “Gospel According to St. James,” his definition of one category of our membership, “amateurs of letters and the fine arts,” as “gentlemen of any occupation provided their breadth of interest and qualities of mind and imagination made them sympathetic, stimulating, and congenial companions in a society of authors and artists.” And he added, tough minded as he was and good lawyer that he was that the Admissions Committee should never interpret the terms as “to cover candidates who do not clearly possess what may be called a responsive sympathy with letters and the fine arts, no matter how eminent or successful they may be, no matter how respectable socially, or how deserving of recognition on special grounds.”

If the Century does not survive as the Century of its first century, it will not be because Harry James did not specify the needed genetic characters. But it will survive and its immortality will be Harry James’.

Source: Henry Allen Moe Papers, Mss.B.M722. Reproduced by permission of American Philosophical Society Library & Museum, Philadelphia

Henry Allen Moe

Henry Allen Moe Papers, 1947 Memorials