Lawyer

Centurion, 1872–1906

Born 12 December 1812 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Died 27 February 1906 in New York (Manhattan), New York

Buried Green-Wood Cemetery , Brooklyn, New York

, Brooklyn, New York

Proposed by Benjamin H. Field and James W. Beekman

Elected 5 October 1872 at age fifty-nine

Archivist’s Note: Nephew of (nonmember) Washington Irving; cousin of Pierre M. Irving

Century Memorial

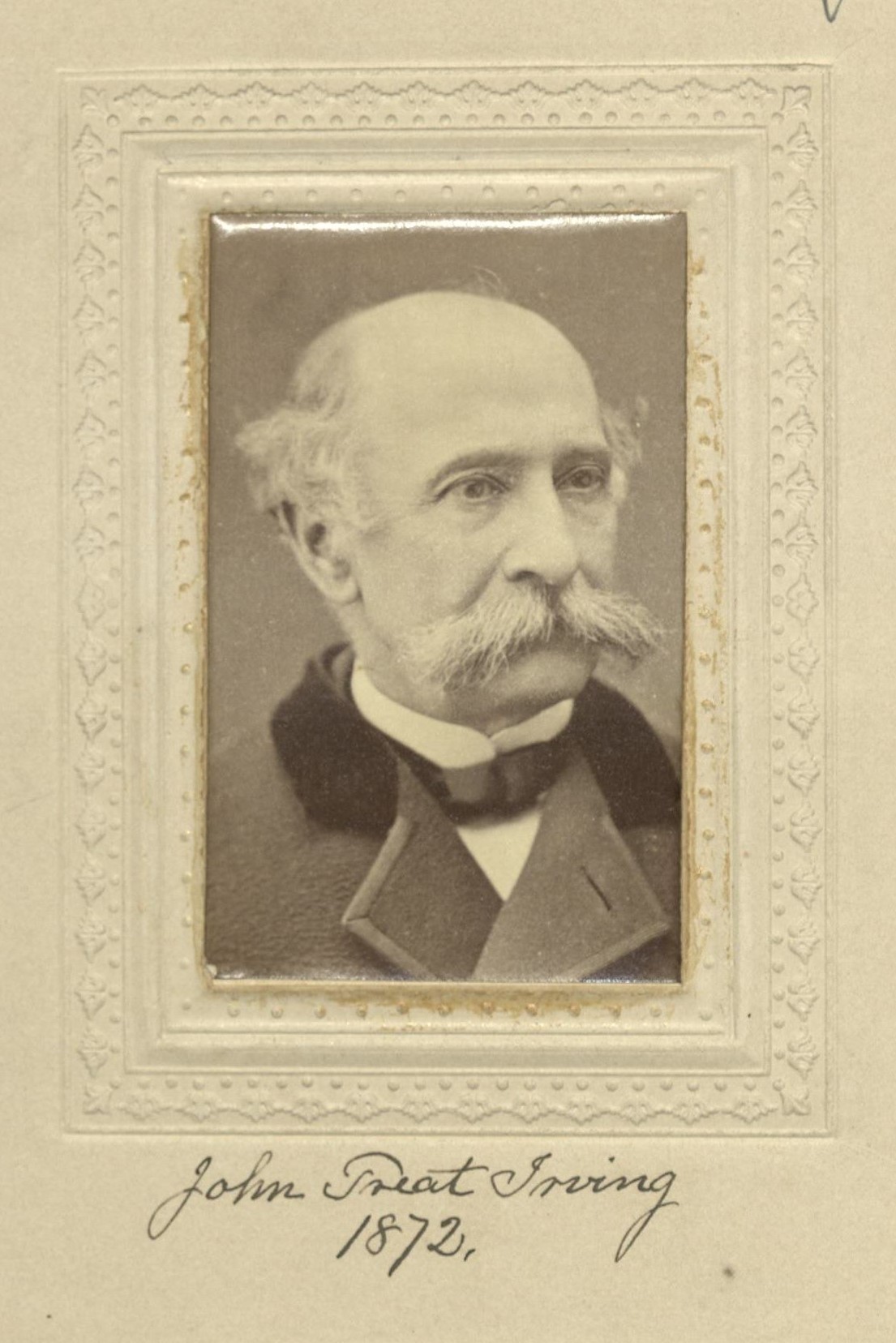

The venerable John Treat Irving, although he had reached sixty [sic: fifty-nine] when he was elected to The Century, was for nearly the duration of an ordinary generation one of the most familiar figures in our rooms. Born in 1812, he studied law and was admitted to the bar, but the literary instinct was in his blood—he was a nephew of Washington Irving—and he cultivated authorship with much zeal and no little success. His “Indian Sketches,” the fruit of his experience with a government expedition sent out in 1833, which he accompanied, are probably the most interesting and trustworthy observations of a phase of national development seemingly as remote from the present as that of the first settlers. They are simple, without a trace of book-making, lively, detailed, and accurate. He made two excursions in imaginative writing, “The Van Gelder Papers” and “The Attorney,” which were marked by like directness and a rare flavor of reality, suggesting, by a certain atmosphere of quiet humor, the spirit of his famous uncle. These traits shone in his conversation, also, and made him a peculiarly welcome visitor at the Club, which he frequented with affectionate steadfastness long after he was able to recall the names of his companions. He was a zealous and skilful chess player, and, in memory of his games with the great Morphy, presented to The Century the table on which they had been played in the rooms of the Chess Club, of which at one time he was the President. Mr. Irving was also an adept at old-fashioned billiards, and retained a sort of instinctive skill in the game when neither eye nor brain could clearly follow it. And one of his familiar antagonists at chess has remarked that, “while memory and personal recognition had failed, from out of the past there remained a remarkable apprehension of every move of his adversary in its effect upon his answering move.” In his later years—he was ninety-four [sic: ninety-three] at the time of his death—his mind was a storehouse of engaging reminiscences of men and things remote from the knowledge of most of us, but vivid with him, and made fascinating to his associates by the modest zeal with which he recalled them.

Edward Cary

1907 Century Association Yearbook